Case Study 6: Lutz Mommartz, Zweileinwandkino, 1968

as part of the exhibition The Invisible Force Behind

Typ

Case studyDate

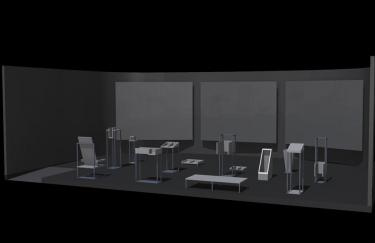

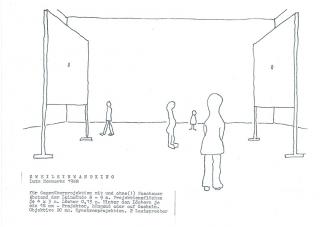

01.01.2014Lutz Mommartz began to shoot experimental films in the mid-1960s and employed multiple projection to depart from the usual cinematic paths for screening films. When Arnold Bode invited the initiators of the Creamcheese artists’ bar in Düsseldorf to open a branch in Kassel during documenta 4, Mommartz exhibited his Zweileinwandkino there. Two large screens stood parallel to each other about ten meters apart and formed the “cinema space.” Installed directly behind each screen was a 16-mm projector that projected the film images through a whole cut in the screen and onto the opposite screen. Two films produced especially for Zweileinwandkino—Gegenüber (Opposite) and Rechts/Links (Right/Left)—were shown, and the action of each film took place simultaneously on the two screens. The scenes on the separate screens were thus linked to each other in the process as if in a dialogue. The viewers were encouraged in this way to connect the events to one another by turning to one screen and then to the other. The space between the screens was thus incorporated as the site of the action.

After the exhibition of Zweileinwandkino in Kassel, and a short time later at the Kunsthalle Bern, the 16-mm stock of the films that formed part of it was largely worn out. A synchronous screen of the films on two screens was no longer possible with these fragmentary strips of film. In the 1990s, in remembrance of the work, Lutz Mommartz produced a video documentation from the remnants of the film.

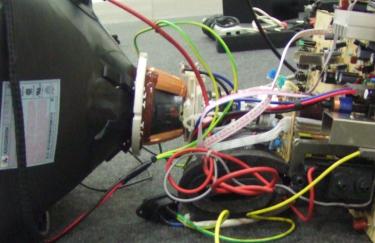

The IMAI Foundation had several discussions with the artist about a possible reconstruction of the work. It was not just about recreating the original spatial installation but above all about digitally combining the surviving remnants of film into a new version that could be played back. The possibility of producing a remake of the film Gegenüber, because little original material of the film existed but a detailed script did. Nevertheless, despite the artist’s precise knowledge and cooperation, it became clear that new filming could not convincingly replace the film. In the time between the first filming of 1968 and the planned refilming in 2013, not least the technical conditions of shooting and projecting a film had changed so fundamentally that adapting to the present would inevitably have led to a different result. The option of a reshooting Gegenüber that could at least begin to convey its artistic idea was ultimately abandoned when Lutz Mommartz unexpected discovered fragments of film in his archive that had long since been thought lost. This rediscovered stock was sufficient to produce, using digital editing and processing technologies, synchronized versions of both Rechts/Links and Gegenüber that preserved the conceptual unity of the original films, despite their shorter running times.

In the case of Zweileinwandkino, it became clear that a remake of the films would not have been authentic replacement. Instead, in the reconstruction the re-edited versions of the original material replace the destroyed original films. For the screening in the installation of Zweileinwandkino, which was based on the original dimensions, a transfer to 16-mm film was urgently necessary so that the use of film projectors would be preserve the essential historical reference to expanded cinema and to Mommartz’s aim to create an expanded cinematic reality.

The case study on Zweileinwandkino examined how to employ digital techniques to preserve and reconstruct film-based works of art. Another essential component \of this example was the discussion of the conceptual dependence of time-based media and the equipment to present them.

The result of this case study are published in:

Renate Buschmann, “Anmerkungen zum Remake des Zweileinwandkino von Lutz Mommartz” and “‘Am schönsten ist das Zweileinwandkino, wenn es nicht in Betrieb ist’: Ein Gespräch zwischen Renate Buschmann und Lutz Mommartz”, both in the book Die Gegenwart des Ephemeren: Medienkunst im Spannungsfeld zwischen Konservierung und Interpretation. Renate Buschmann, “Eine Vision von Kino” in the exhibition catalog The Invisible Force Behind: Materialität in der Medienkunst.