Case Study 1: Studio Azzurro, Il nuotatore (va troppo spesso ad Heidelberg), 1984

Part of the IMAI Restoration Project

Typ

Case studyDate

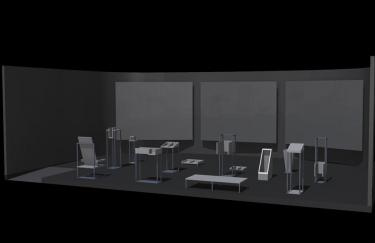

01.11.2006Il nuotatore (va troppo spesso ad Heidelberg)—in English: The Swimmer (Too Many Trips to Heidelberg)—of 1984 is one of the most important works by Studio Azzuro, an artists’ workshop founded in Milan in 1982 by Fabio Cirifino, Paolo Rosa, and Leonardo Sangiorgi. In this video environment, a swimmer swims his laps nonstop. As he does, he seems to be breaking through the fames of twelve side-by-side monitors. An additional monitor shows moving images of a clock, some of which are distorted. A blue light saturates the ambience and lends the installation the atmosphere of an underwater world. The visual impressions are supplemented by the sounds of water, music, and a reading of the story “Too Many Trips to Heidelberg” (1977) by Heinrich Böll.

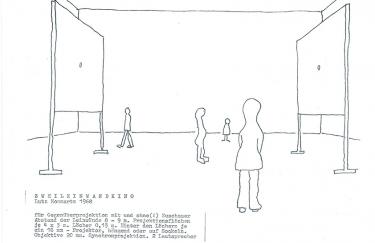

At the first performance in the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice (1984), two rows of twelve monitors each for the videos of the swimmer were placed in a room designed as an indoor swimming pool. This first presentation was followed by numerous repeat performances. All of them reduced the monitors to a single row of twelve. The swimming pool was not built again. The videos of the swimmer were transferred to laserdiscs in the 1990s. New systems for their synchronization were tested. After an extended playing time, however, the twelve videos would go out of sync anyway.

- What role do place (cultural, historical, social references, conditions of the space) and presentation (suggestion of a swimming pool, guiding of visitors, number and position of the monitors, light, sound, etc.) play in The Swimmer?

- Which qualities of the work are crucial to its authenticity?

- In what state are the original U-matic tapes and the laserdiscs from the 1990s? Should the video be digitized and, if so, from which material: U-matic or laser disc?

- How can one prevent the twelve videos of the swimmer getting out of sync? What significance do tube monitors have for the work’s effect?

- Is it permissible to replace them with flat screens?

Media Storage:

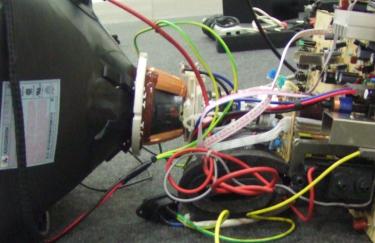

While evaluating the video material during the case study, specific signs of aging of the two data storage media used (U-matic tapes and laser discs) could be identified: Whereas the U-matic were primarily affected by dropouts, the laser discs had typical large-area flicker and a low-contrast and out-of-focus image compared to the original U-matic tapes. In addition, it turned out that the laser discs have an abridged version of the videos. Both versions were secured and all the storage media cleaned. For the presentation at IMAI, MPEG-2 video files were also produced and stored on compact flash cards.

Synchronization:

A twelve-channel MPEG player with integrated control software was used to present the work. This permitted long-term synchronization, in contrast to the version with twelve U-matic- or laser disc players.

Re-Screening:

The IMAI Foundation presented The Swimmer again by showing it in the exhibition Crossing the Screen (30 Nov. 2006–14 Jan. 2007). The presentation in Düsseldorf was based on the form that had become established in the previous reinstallations.

Venue and Presentation:

From an art historical analysis of the work and an interview with the artist Leonardo Sangiorgi it was apparent that the installation was not conceptually tied to its first exhibition venue. The first presentation of The Swimmer was unique: visitors could “dive” from stairs into a kind of swimming pool and wander around the monitors. According to Sangiorgi, constructing a swimming pool was not a requirement for subsequent performances. This new form of presentation did, however, essentially alter the experience the work could offer the viewer. The ambience with blue light, sound components, and the separate video sequence with the clock play a fundamental role in the video installation.

Monitors:

One essential aspect for the authenticity of the installation is that the image of the swimmer must be larger than the frames of the individual monitors. The number of monitors is not absolutely fixed. Doubling the row of twelve monitors is not necessary, according to Sangiorgi. Sangiorgi is of the view that the tube monitors could in the future be replaced both by flat screens and by projections. Both possibilities would, however, be questionable from the perspective of art history and conservation ethics because they would result in a substantial change in the aesthetic and in particular sculptural qualities of the installation.